- Home

- Christian Schoon

Zenn Scarlett

Zenn Scarlett Read online

Christian Schoon

ZENN SCARLETT

To Kathleen, my favorite life form.

BEFORE

Wind clawed at the canvas tarp covering Zenn in the cargo bed of the ancient pickup truck. The truck picked up speed, rattling and bucking down the rutted dirt road, and it took all her strength to keep the coarse cloth from being ripped out of her hands. But more speed was good. It meant her father and Otha hadn’t noticed her hiding beneath the tarp… yet. The truck hit a bump; she lifted several inches into the air, then came down painfully against the rusty surface.

Never leave the cloister.

That was the first rule, the important rule. Bad things happened outside the cloister walls. Frightening things. Lurching and bouncing in the back of the speeding truck, Zenn was fairly certain she was already as frightened as it was possible to be. But breaking the first rule was only part of what made her heart leap inside her like a cornered animal. The other fearful thing floated somewhere far beyond the Martian sky above – a starship. Inside it was an Indra, one of the biggest, most astonishing creatures in the known universe. And trapped inside the Indra’s body was Zenn’s mother.

Zenn knew something was wrong the moment her uncle rushed into the cloister yard earlier that morning. He was breathless from running. Otha was a big man, and he seldom ran.

“Warra, it’s Mai,” Otha said to her father. “It’s serious. You’d better come.”

Predictably, her father said she would have to wait with Sister Hild at the cloister compound while he and Otha drove to Arsia City and took an orbital ferry up to the starship. Zenn had protested, had even cried a little. It didn’t help. She was to be left behind. But when Hild was busy filling bowls, tubs and other containers with food for the morning feeding of the animals currently among the clinic’s menagerie of patients, Zenn had quietly slipped out the side door of the refectory kitchen.

Now, breathing dust and bio-diesel fumes beneath the tarp, her uncle’s words circled in her mind. How serious was “serious”? Zenn was well aware her mother dealt with many kinds of large, dangerous alien animals, including the enormous Indra. Her mother was an exoveterinarian; that was her job. This Indra was sick. And her mother had gone into its body to cure it. Then something had gone wrong. Very, very wrong.

The truck hit an especially deep hole in the road, tossing Zenn so high she was almost thrown out the back. She forced herself not to think about what would happen to her if she fell out, even if she survived the impact. People caught alone, out beyond the cloister walls or the safety of villages, were being robbed of anything they carried: money, food, supplies, even their shoes. Some were beaten when they resisted, a few had been killed, if the stories could be believed. And with every story, it seemed to be getting worse.

Never leave the cloister.

Another vicious bump and her head banged down hard. The rough fabric of the wind-whipped canvas bit painfully into the skin of her fingers, and the acrid exhaust smell was making her feel sick. Then, thankfully, the truck slowed, the wind died. They must be close to the ferry port outside Arsia.

A minute later, the truck turned sharply and skidded to a stop. Two doors creaked open and slammed shut. Zenn threw off the tarp and stood, releasing a cloud of fine, red dust. Her father and Otha were striding toward the ramshackle hut that passed for the launch pad’s control tower.

“Dad!” she yelled, her voice cracking.

It’s serious. You’d better come.

He couldn’t go without her. That’s all there was to it.

“Dad!”

Her father was angry, of course. She’d expected that. But there was no time to drive her back to the safety of the cloister, so they had to take her with them.

Just nine years old at the time, Zenn wasn’t really surprised that now, thinking back on it, she recalled little about the ferry ride into orbit or their arrival at the starship. She did remember the ship was vast, bigger than anything she’d ever seen. Her next clear memory was of the piercing, almost shocking cold inside the ship’s pilot room. She recalled clearly the air there was cold enough to turn her breath into spheres of ice-crystal mist that formed and disappeared like tiny, glittering ghosts.

The pilot room was a long, low, dimly lit space. The walls flickered with lighted dials and screens, and there was a strangely sweet, smoky scent in the air that seemed somehow out of place in the frigid room. Zenn saw that the scent arose from a bundle of smouldering twigs on a tiny stone altar set into an alcove on one wall. She realized this was the incense her mother had told her about; it was burned in the pilot room as part of the secretive rituals conducted by those who attended the Indra.

A large chair sprouting odd machinery and wires was mounted on some sort of swiveling base in the center of the floor, and a viewing window filled most of one wall. The window looked out into the Indra chamber. From her mother’s stories of treating other Indra, Zenn understood that this was the place the animal would come when it was called to by the starship pilot, the Indra groom. Then the Indra would take the starship to its destination. Young as she was, Zenn had no inkling how this was accomplished; but she did know that since Indra ships were the only means of travel between the stars, Indra were very important creatures.

Zenn’s father and Otha were talking to a tall woman dressed in a close-fitting bodysuit of a cloth that shone like metal. The patches on the shoulders of her uniform, and the shifting pattern of animated tattoos visible on her neck and face, identified the woman as the starship’s Indra groom.

For a moment, Zenn stood staring at the many metal rings, tiny chains and jeweled studs the groom wore on her face and in her ears. Then movement caught her eye. She went to stand on tiptoes at the viewing window – and gasped at her first glimpse of a real, live Indra. The animal’s head, big as a hay barn, was all she could see. The rest of its colossal body coiled off into the shadowy recesses of the chamber.

Of the many facts Zenn’s mother imparted to her about the Indra, two stood out: the Indra’s size, and how the creature got its nickname, Stonehorse.

“Indra are among the largest animals in explored space,” her mother had said during one of these talks. She showed Zenn a v-film drawing of an Indra. To indicate its size, the creature’s legless, slightly flattened serpentine body was drawn next to a starliner. “Indra grow to be over seven hundred feet,” her mother continued. “See? It’s almost a quarter the length of the starship.”

Zenn was puzzled by this. It didn’t seem possible such a big animal could be contained in the ship and still leave room for any passengers.

“How does it fit?” she’d asked.

“Good question.” Her mother pointed to one end of the starship. “See how the ship bulges out at the back? That’s the Indra warren. It curves around inside, like a giant seashell. The Indra lives in the curving tunnels of the warren.”

“Why does it live there, in a ship?”

“In the wild, Indra live inside the caverns of asteroids. When the Indra wants to travel somewhere, it does something called tunneling. Well, Alcubierre null-spin quantum tunneling, but that’s kind of hard to explain. What’s important is that the Indra have evolved the ability to move very long distances through space in a very short time. When the Indra does this, when it tunnels, it carries its asteroid home in front of it. The nickel and iron metals in the asteroid act like a shield, to protect the Indra from dangerous particles in space. Long, long ago, a race of beings that no longer exists figured out a way to harness the Indra to propel starships. To make the Indra feel at home in the ships, they built the warrens to be like caves in an asteroid. In fact, in an old language called Latin, the Indra are called Lithohippus indrae. Litho means stone. And hippus means horse. That’s why some peo

ple call the Indra Stonehorses.”

Zenn liked that the Indra had this nickname. On the one hand, it was comical, since an Indra’s body looked nothing at all like Earther horses. But on the other hand, the fact that the Indra took starships to other places was just like a horse taking a wagon somewhere.

At the moment, the Stonehorse Zenn was looking at floated in the zero gravity and airless vacuum of its chamber. The scales of its armored skin gleamed gold and red, its face covered in tendrils that waved slowly to and fro. The creature’s head, she had to admit, did look vaguely like an Earther seahorse, or possibly like a sleepy, fairytale dragon. Impossible as it seemed, her mother was inside this animal. And she couldn’t get out.

Behind Zenn, Warra Scarlett’s voice rose. He was almost yelling at the tall woman now, and this was enough to pull Zenn’s attention from the Indra. Her father never yelled. He was asking how the groom had lost contact with her mother, something about backup systems and how they were not supposed to fail.

Also in the pilot room was a short, stout, gray-haired man in an all-white uniform. Otha addressed him as captain. The captain tried to calm her father, but it didn’t seem to have much effect. Her father said that her mother’s assistant, Vremya, should be able to help get her mother out of the Indra. Zenn looked into the chamber again and saw that the assistant was floating high up at the back of the huge room, wearing a helmeted vac-suit as she bent over a small console tethered to the wall next to her.

The groom explained to her father that Vremya had tried to help, but for some reason she was unable to make contact with the pod carrying her mother. Then the groom waved one hand and a virtual readout screen shimmered to life in the center of the room. Zenn moved in closer to see the virt-screen better – and to be nearer to her father as the voices in the room grew more urgent and upset.

On the virt-screen, the outline of the Indra’s upper body glowed as a sort of three-dimensional x-ray. Just below the point where the Indra’s long body joined the seahorse head, Zenn could see a small, oval-shaped blinking light – the in-soma pod that held her mother. With every blink, the pod moved a little closer to the Indra’s head.

Otha pointed to the blinking dot and said the in-soma pod wasn’t working correctly; that it was carrying her mother toward the Indra’s skull. He said the pod was only designed to travel in certain parts of the animal’s body. Just hearing Otha’s steady voice and calm, matter-of-fact explanation of the situation made Zenn feel a little better. Otha had assisted her mother during other in-soma pod insertions into Indra. He knew the animals almost as well as Mai. If anyone could help her mother now, it was her uncle.

“If the pod reaches the Indra’s skull,” Otha said then, “it will trigger a lethal spike in Dahlberg radiation.” Zenn’s father shook his head, not understanding. “It’s surge of quantum particles. A by-product of the Indra’s tunneling ability. It’s a protective mechanism – something like an immune response.” Otha gave her father a look. Zenn could tell from this look, and from Otha’s tone of voice, that this was a bad thing.

Her father became even more excited and angry then, and was speaking very fast to the groom when a loud alarm blared through the room. Everyone turned to the viewing window. They saw the animal seemed to be in distress, or some sort of pain. It shook its massive head up and down, back and forth, as if to rid itself of something. Flashing emergency beacons came on, bathing the Indra in stark, intermittent bursts of illumination.

Then a blinding, blue-white surge of light exploded out from the Indra. Zenn clapped her hands over her eyes. Another flash, even brighter, was visible through her fingers. And, at that moment, a feeling unlike anything she’d ever felt flowed through her. It was a sort of dizziness; a sudden warmth, a feeling she might faint. But more than that, it was a feeling that her body was no longer her own, familiar body. The odd sensation ran through her like an electric charge, and then vanished as quickly as it had come. It was, she thought later, probably just a reaction to the fear and confusion that gripped her. It was as if some part of her knew what was happening to her mother; knew but didn’t want to know.

Everyone was shouting then, and a very bright, blue-white glow streamed steadily from the Indra chamber into the pilot room. It appeared to Zenn that no one there knew what to do, and this scared her more than anything. A deep, grinding sound came from the ceiling, and a thick slab of dull gray metal began to slide down to cover the viewing window. The groom yelled for them all to move back and a second later the slab hit the floor with an impact that shook the room.

“No!” her father cried, turning to the woman. “We can’t see into the chamber. We need to see.”

Zenn ran at the metal slab that now stood between her and the place where she knew her mother was in unspeakable danger. Zenn pounded on the cold, hard surface of the metal, but it didn’t move. She screamed – she couldn’t remember if she screamed words or if she just produced some meaningless sound.

“The blast shield deployed automatically,” the groom said, not looking away from the multiple virt-screens now dancing in the air around her. “It will remain in place until levels are safe again.”

“Levels?” her father shouted. “What levels?” She didn’t answer him.

The alarm continued to blare for a few seconds more, then cut off. The groom stood very still, staring at the virt-screens.

“No…” she said quietly to herself, as if she didn’t believe what the screens showed her. “It cannot be…”

The blast shield rumbled to life and lifted back up into the ceiling. They all waited. No one moved or spoke. When the shield was halfway up, Zenn ran and ducked under it. She rushed to the viewing window, strained to see into the room beyond. The walls smoked as if swept by some terrible fire. Except for the smoky haze and flashing emergency lights, there was nothing to be seen. It was empty. Completely, horrifyingly empty.

“She is gone,” the groom said, her voice low and strange. “My Stonehorse… gone.”

Her father stared through the viewing window. He covered his eyes with one hand, and then looked again. Otha reached out and put a hand on her father’s arm.

“Otha…” he said. “What happened?”

“I don’t know, Warra,” her uncle said. He looked out to where, moments ago, the Indra had been. “This shouldn’t… I’ve never seen anything like it. I’ve never heard of this sort of reaction. I don’t know what to say. Warra… I’m sorry.”

Zenn stood at the viewing window, her breath visible, rising and dying before her, fogging the glass. Her father came to stand next to her. He lifted both hands to lay them flat against the window’s surface. After a moment, he turned, reached out and brought her body in close to his. She pulled back just a little, so she could see his face, so she could see what this all meant, see what she should say, or do, or think. In the biting cold of the room, tears cut hot trails down her cheeks.

The one thing she did remember quite clearly from that day was what her father said next.

“It’s alright, Zenn,” he told her, looking at her but not seeing her, as if seeing something only visible to him, “…we’ll be alright.”

She knew her father meant what he said. He didn’t mean to lie. He was just wrong. But in the years to come, it wouldn’t be Warra Scarlett’s fault that their life did not even approach being “alright.” When things finally went from merely sad to utterly catastrophic, Zenn was quite certain of one thing. The fault… was hers.

ONE

Zenn could see herself reflected in the gigantic eyeball, as if she stood before a gently curved, full-length mirror. She didn’t like what she saw. It had nothing to do with being inches away from a two-foot-wide eye – she’d seen bigger eyes. It was the odd angle of the tank-pack strapped to her back. She hadn’t noticed before – she was too preoccupied with getting into position on the bridge of the whalehound’s nose. But her reflection revealed the pack was sagging badly to one side. It could pull her off-balance if the animal made any su

dden moves.

This I can fix, she told herself. Just don’t let anything else happen. Please, don’t let that… other thing happen.

She tugged at a harness strap to center the pack between her shoulders, but the motion startled the hound. He blinked and flinched, and she wobbled violently, arms flailing. Her foot slid on the slick fur – she was going to fall off. Her hand closed around something – an eyelash thick as a broomstick. A quick pull brought her upright again. She let go of the lash as though it were a red-hot poker and froze.

Had she spooked the animal? Tense seconds passed. But the hound just regarded her calmly with his one good eye, huffed out a low groan and was still; waiting to see what the spindly little creature on his snout would do next.

She glanced at Otha on the pen floor thirty feet below. Apparently, he hadn’t noticed her misstep. That was a first. He was intent on monitoring the whalehound’s vitals and the sedation field, his attention on the virt-screens hovering before his face like oversized, translucent butterflies.

Congratulating herself on a disaster averted, Zenn risked a few extra seconds to savor the view from this novel vantage point. Stretching away below her, the hound’s sleek, streamlined body reached almost to the far side of the hundred-foot holding pen. Still damp from his morning swim, the animal’s thick, chocolate-brown fur released wisps of steam into the cool Martian air. Beyond the holding pen, the view encompassed most of the cloister grounds – over the clay-tiled rooftop of the infirmary building to the refectory dining hall. Looking past the open ground in the center of the cloister walk, Zenn could see all the way to the crumbling hulk of the chapel ruins. The chapel, like most of the cloister’s earliest buildings, was a massive, handsome structure constructed of large sandstone blocks quarried from the canyon walls. The more recent buildings, on the other hand, reflected the changing situation on Mars. Harvesting and transporting huge chunks of stone was energy intensive. Accordingly, most of the buildings put up in the past few years were made from any materials that could be scrounged, salvaged or recycled.

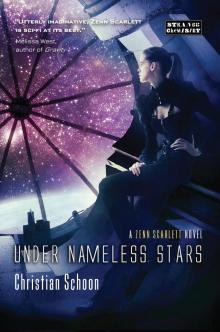

ARC: Under Nameless Stars

ARC: Under Nameless Stars Under Nameless Stars

Under Nameless Stars Zenn Scarlett

Zenn Scarlett